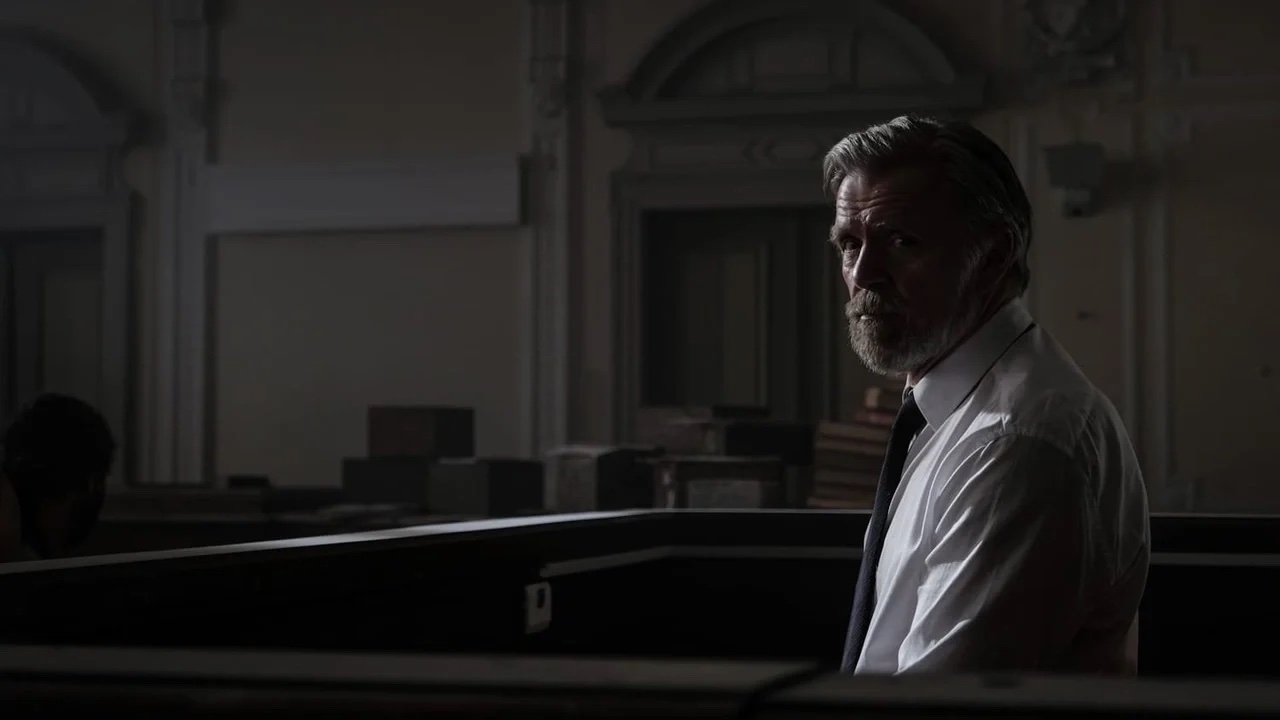

A film of great intelligence especially visual and gestural.

Ettore Scola Award for Best Director Bif&st 2023, The man without guilt is a bilingual work that communicates above all with silences.

In the Slovenian suburbs of Trieste, Angela has lost her husband Andrea to asbestos exposure and knows that her friend Elena, also a widow, will meet the same end. She dreams of the Slovenian word – the mother tongue of her husband who, we discover later in the film, is actually called Andrej Rusič – which stands for “dust” repeating itself in an almost liturgical litany. In the nursing home where she works, an elderly woman advises her not to “lose your head” because she “once lost, she is never found”.

The discovery that the builder for whom her husband worked, responsible for the failure to make the workplace safe and, consequently, for the death of many of his workers, had a stroke that compromised her motor and verbal faculties prompts her to introduce herself in the life of the man, cared for by his son, with the aim, perhaps, of taking revenge. Thus, she agrees to become her personal nurse and to establish a relationship with him, which becomes more and more intimate up to the extreme erotic consequences. Does hate become love? Impossible to give a definition to feelings that the film, with great dramaturgical finesse, gives us mobile, punctuated by an accent of pietas, opening up to the most diverse affective modulations.

The man without guilt: after the non-fiction, another study on the body and its boundaries

The man without guilt is a film which, in the end credits, asks for justice for the thousands of people who die every year because they develop respiratory diseases, often oncological, caused by exposure to asbestos fibres. However, it is not a civilian film. Tense, poetic, but with a toned down, never lyrical poeticity, with a powerfully existentialist vocation, it stages an encounter: that between a woman who is mourning and the man who, for that mourning, is responsible. Recited a little in a covered-up Italian of Trieste and a little in Slovenian, it communicates above all in silence, through the non-verbal language of tensions and body spasms, of the overlapping of movements – controlled, thoughtless, almost always abrupt and even angry, whether it’s restrained or explosive anger – of the two protagonists.

The director, born near Gorizia in 1977, has always been interested in studying the self in and with the body: a few years ago he made Dancing with Maria, a documentary about the therapeutic use of dance by Maria Fux, a Argentine dancer and teacher who has adapted the techniques and grammars of the dance language to the integration of people with disabilities and to the acceptance of the bodily limit and its unexpected openings. In the work dedicated to her, Maria Fux finds herself, in fact, measuring herself not only with the ‘inclusive’ mission carried out throughout her life, but also with the ‘fall’ of her own body. Here too, in this film, there is a woman – played by the extraordinary Valentina Carnelutti – who is a body exposed to bodies: the crippled one of a patient and her own, object, despite the mortification inflicted on her by pain, of other people’s desire, not just passively welcomed or offensively rejected. In the space of interaction and collision, in the intermittences of perceptions and feelings, between these two protrusions – the protrusions, the extra that bodies always represent for us and with which we identify and disidentify ourselves so with difficulty – the highest discourse is generated of Gergolet’s film representation: the porosity of borders, not only between peoples – Trieste is precisely a border city, a land of cultural contamination between Slavic, Latin and Germanic peoples -, but also between the opposing moral principles of good and evil, guilt and innocence.

The man without guilt: conclusion and evaluation

The man without guilt therefore turns out to be a film of great intelligence, especially visual and gestural: the writing of the dialogues is, in fact, more humble and less effective than the ‘score of silence‘, created with extremely eloquent results. Approaching it requires attention in its etymological sense: the willingness to participate in an unhurried, silent and devoted faith in a superior artistic design, the one that, only at the end, discloses its symmetries and its ultimate meaning. The actors, deprived of the ‘word’, make a journey back to the radical nuclear nature of their experience as animals enmeshed in civilization and, thus, even guilt slips, from the moral plane, the edification of men to the confrontation with values conditioned by culture, in more authentically affective dimension. Only in this land of pure feeling, the anger of the characters for what they have lost – health, love, identity – can be transformed into a profound understanding of the fallibility and transience of the human, this first step towards acceptance of one’s own and others’ limits and towards an indulgence that has nothing to do with passivity or defeat. Only in the evaporation of evil and its contours that would claim to be absolute, is it possible to reach some form of salvation. Or even just a temporary peace. Be it in death or in a life that continues, and, in the body, understands its necessity.

Source (in italian): cinematographe